Kool Stuff[8]: Rob Holmes on the End of Acclaim's Relationship with Midway

This post is part of Kool Stuff, a companion book to Long Live Mortal Kombat: Round 1 (now on Kickstarter!) that contains interviews I was unable to do before hitting Long Live MK’s deadline. Subscribe to Episodic Content to keep up with news on Long Live MK, and to follow along with Kool Stuff as new chapters are published.

[Author’s Note: Welcome to another chapter of Kool Stuff! This week’s content works a little differently. First, you should head over to Game Developer and read my interview with former Capcom USA senior VP Joe Morici on the marketing feud between Capcom USA and Acclaim. That interview ties into today’s Kool Stuff chapter, which you can read below. Finally, if you haven’t supported Long Live Mortal Kombat’s Kickstarter yet, be sure to check that out. Thank you for your support!]

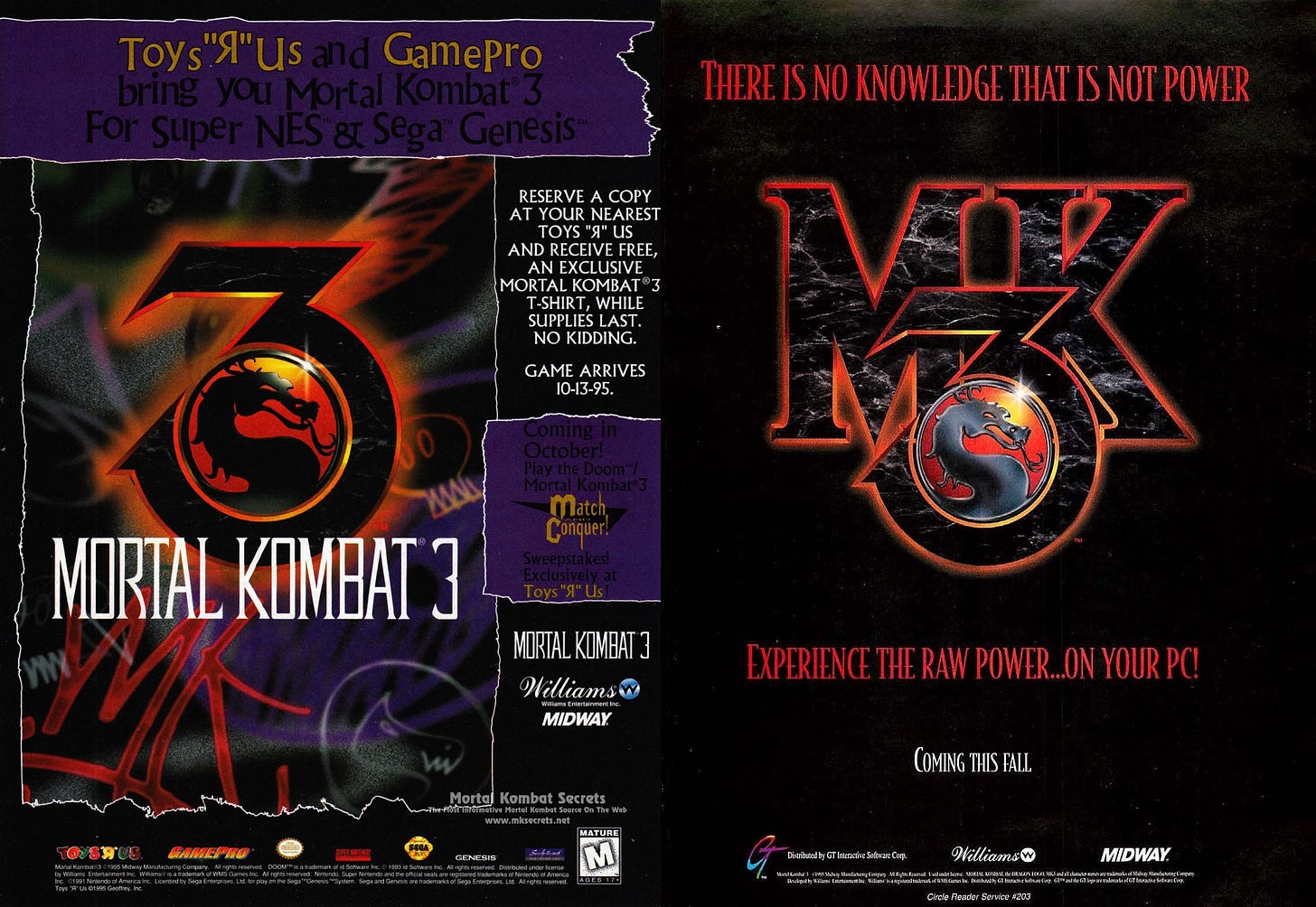

All good things end. Rob Holmes and his fellow Acclaim co-founders, Greg Fischbach and Jim Scoroposki, knew their licensing deal with Midway, which gave them the right of first refusal to bring coin-op games like Mortal Kombat and NBA Jam to home systems, wouldn't last forever. Midway boss Neil Nicastro was monitoring the home market. He saw how much money Acclaim was pulling in from home ports of his arcade games. Nicastro got a cut of royalties, but why settle for a cut when his engineers and artists were the ones making the coin-ops, the source material, in the first place?

Rob Holmes talked to me about when he knew Midway would be moving on from Acclaim and provided his perspective on the rivalry between Street Fighter and Mortal Kombat.

Craddock: I devoted a chapter in Long Live Mortal Kombat to the divide between MK and Street Fighter II players. I was surprised to find out that competition spilled over into the publishers. Specifically, there was an issue of Capcom's Street Fighter II comic book featuring a Mortal Monday ad. How did that happen?

Holmes: Yeah, they sort of screwed up. I think it was Holly Newman or someone at our ad agency that altered me [to the SFII comic having ad space available], and we were able to lock down the back cover of their comic. That didn't please them, but it did please me. Joe Morici [senior vice president at Capcom USA] and I were buds. We were competitors, but everybody was friendly, at least where the third-party publishers were concerned. Joe and I were around at the very beginning of the 8-bit business. I remember meeting him at the first CES we attended, where we had a single monitor in Nintendo's booth. We got friendly and got a beer, and by the next time around, we had a full station at Nintendo's booth, and then two, and so on.

“Our relationship stayed friendly, but it got really, really awkward for a while.”

Joe was quick to realize Acclaim was growing, but he was at Capcom and had another agenda. Not to sound ethnocentric, but that was true of a lot of Japanese companies operating in the US. Dating back to [senior VP] Emil Heidkamp at Konami—Emil was trying to get Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles [the arcade game] to the US, but he had to ram the idea that it would be successful in the US down Konami's throat because most Japanese companies were very focused on the Japanese market: they were focused on arcades, and they were focused on Famicom. The individuals at the US branches of these companies were spending a lot of time on planes, taking whatever materials they might be given and presenting them.

Acclaim had the advantage of a different background. We had a very creative marketing group. We had people with experience in toys, wine, and technology, all varied industries, so we approached things differently. We looked for competitive areas in which to do that. So when that issue of the Street Fighter II comic was printed and put on my desk, I picked up the phone, called Joe, and said, "So... love the comic. What do you think?"

Craddock: I spoke often with Midway's coin-op manager, Ken Fedesna, for my book, and he spoke on behalf of Neil Nicastro. He admitted Midway was focused on arcades and that at first, they saw Acclaim's home games as another revenue stream and not much more. Their stance was, "Arcade games have the best hardware, so we'll always have the best versions of our games even though people can buy them for consoles." As home hardware caught up, they said, "We want to acquire a company and port our games in-house so we don't have to share as much money," and that led to them acquiring Tradewest. According to Ken, Midway wasn't interested in renewing Acclaim's deal, and they knew that pretty far ahead of renewal. How did Acclaim view that? Were you concerned about losing the MK and other Midway licenses?

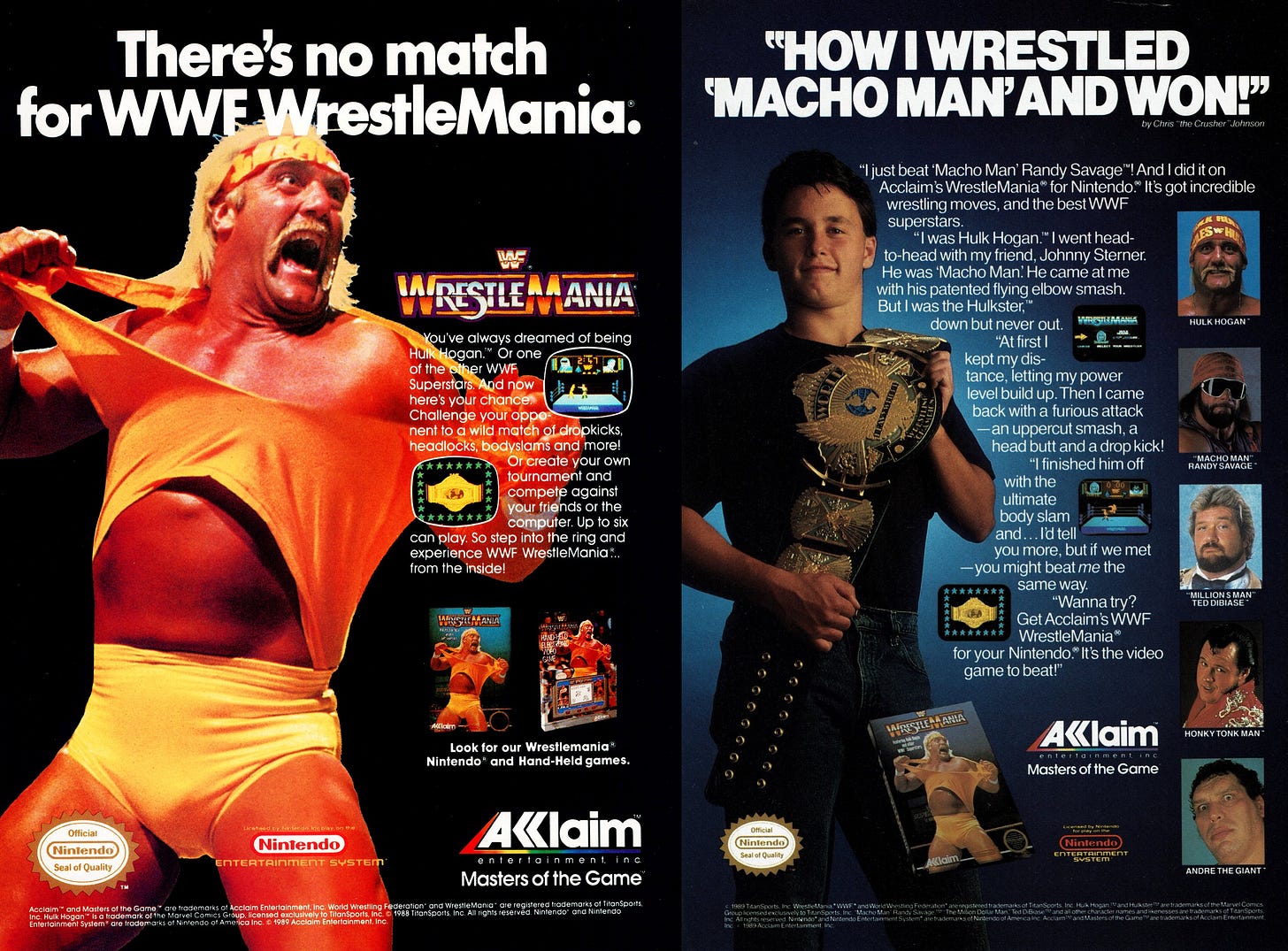

Holmes: Absolutely. It was a huge issue, and the timing was a huge issue. There was a lot of discussion between us and Williams [aka Midway], and to some extent, we were victims of our own success when it came to their games. Neil Nicastro got lucky. We started as nothing, and then all of a sudden we had Hulk Hogan on the cover of a video game [1989's WWF WrestleMania for NES]. Acclaim was an upstart that became the number-one American publisher, and here's this guy, Neil, with a bunch of arcade games. Mortal Kombat and NBA Jam were nowhere in sight at that point, so Williams connected with us and thought, "Maybe we can make a few bucks from this deal." That's what it came down to.

“Do I think home ports released later would have been more successful? Yeah. I think Acclaim would have done a better job.”

We had lots of conversations, and they all came back to our licensing agreement. The original agreement—I'm testing old memories—called for guarantees in royalties based on the install base of an arcade game at the time of signing. So, if their arcade game sold 500 units in the North American market, that generated X amount of dollars as a guarantee. At first, I don't think they were expecting much of anything from our ports. We had Arch Rivals and some other arcade games, like Smash TV. They were shocked because all the sudden, they started getting checks. We were thinking, God, when are these guys going to do something meaningful? I knew Mark Tramell [lead designer of Arch Rivals and NBA Jam] from my Activision days and a few other people and got to know them.

Then along comes Mortal Kombat, which was revolutionary not just in terms of what it did in the market, but for Williams. When those numbers went off the charts, that's when we had the first conversation I remember with them saying, "Gee, maybe we should pull ports in-house." Neil realized what he had on his hands, and when he saw the royalties coming in from other games, when he was making more money from licenses, we said, "Just because you're making a little money, don't forget how hard it is to be in this business." When they started looking at the dollars and personalities we had marketing and porting these games, he realized how it was a developer's world and a completely different marketing approach [for consoles compared to arcades]. They were pretty much the only American name in town at that point, other than games like whack-a-mole and laser tag.

As technology advanced to where he was just sharing source code and trying to develop it down to the constraints of home hardware, for lack of a better way to put it, it got really awkward in a few ways. As these conversations were going on, Acclaim was grappling with, "What do we owe in terms of public disclosure? We're a public company; we've shared the redacted contract [between Acclaim and Williams] so everyone knows when it will run out and when it comes up for renewal." This would have been the third round. There'd been an interim renewal earlier. What should we do? What should we say?

We had quarterly conference calls, and I think this was in February 1994. And there were programmers from Williams on the call, and probably Neil and Ken listening in silently. The programmers started acting like juveniles. They were bluntly saying, "What happens if Acclaim does its own stuff? If you don't have Williams, do you have anything?" These were questions being asked while we were on the phone with all these financial who's-who people. That wasn't cool. I was sitting in a hotel room, angry, just listening to these programmers. And not number-one guys, either; they were a bunch of graphics-on-level-three guys saying, "Neener-neener!" God. That's just not how this works.

The good news at the time was that we had other products to announce, a variety of other licenses, but we couldn't answer those questions, and the Williams programmers knew that because the contract had not been voided. The contract wasn't up, and they had not renewed, but it was pretty clear after that call that a renewal wasn't going to happen, at least to me. We could keep negotiating with Neil Nicastro all we wanted, but—and I'm not pointing fingers at anybody; I don't know who the programmers were—but if they felt comfortable enough to do that, well, it was a fair assumption that things weren't going to go Acclaim's way.

The other part of my attitude at that point was, "So what? Good luck with your marketing. Yes, we like your titles, but you try putting $10 million on the table, rolling the dice, and seeing what happens. You're a public company. You've got a long history. You've got reporting to make public, too."

Our relationship stayed friendly, and it's friendly to this day. I've got nothing but good things to say about Neil, Ken, and everybody else. But it got really, really awkward for a while. And bear in mind, this happened when MK1 [on home systems] was a screaming success and MKII ports were on the horizon. Everything was coming up roses for everybody. Yet there was this dissonance in terms of, okay, we're going to work together on what we have today, but what do we have for tomorrow?

“Neil probably realized it was time to align Williams with another company, and that was where Tradewest came into the picture.”

That also was why, in certain instances, there was no real debate about giving legacy rights to titles we'd released. It wasn't like they were going to recapture the rights to Arch Rivals, for example, or MK1. There were also distribution concerns; Williams knew they weren't set up to do much of anything in Europe or, god forbid, Japan. They didn't have the wherewithal or, frankly, the interest, because that was a mountain too high.

Neil probably realized it was time to align Williams with another company, and that was where Tradewest came into the picture. Tradewest had had a fair amount of success [porting coin-op to home platforms] in the North American market.

So, yeah, every day was a negotiation. At first, Williams was coming out with what were frankly crappy arcade games that didn't earn much and we were still picking them up just because it was like, "Let's renegotiate because we're paying too much." As things got better, it was like, "Okay, we now have an equitable table." Then when things inverted, it was Williams saying, "We think we'd like a bigger piece of the pie."

And more power to them. They figured out a way to do it. Do I think the home ports of games released later would have been more successful [if Acclaim had marketed them]? Yeah. I think Acclaim would have done a better job. Not necessarily with porting the programs, but in terms of the overall marketing package. But I'm biased.

This post is part of Kool Stuff, a companion book to Long Live Mortal Kombat: Round 1 that contains interviews I was unable to do before hitting Long Live MK’s deadline. Subscribe to Episodic Content to keep up with news on Long Live MK’s Kickstarter (set for March 29) and to follow along with Kool Stuff as new chapters are published.